Over the last decade, choosing a new television has become increasingly complex. The advent of 4K has introduced many consumers to the issue of resolution for the first time, while HDR (High Dynamic Range) has moved the issue of backlighting (what type, if any) to the fore. Making these improved features understood by customers is a primary challenge for today’s sales staff.

But these advances are readily explainable in comparison to the most revolutionary development in TV since plasma, the organic light-emitting diode, or OLED, television.

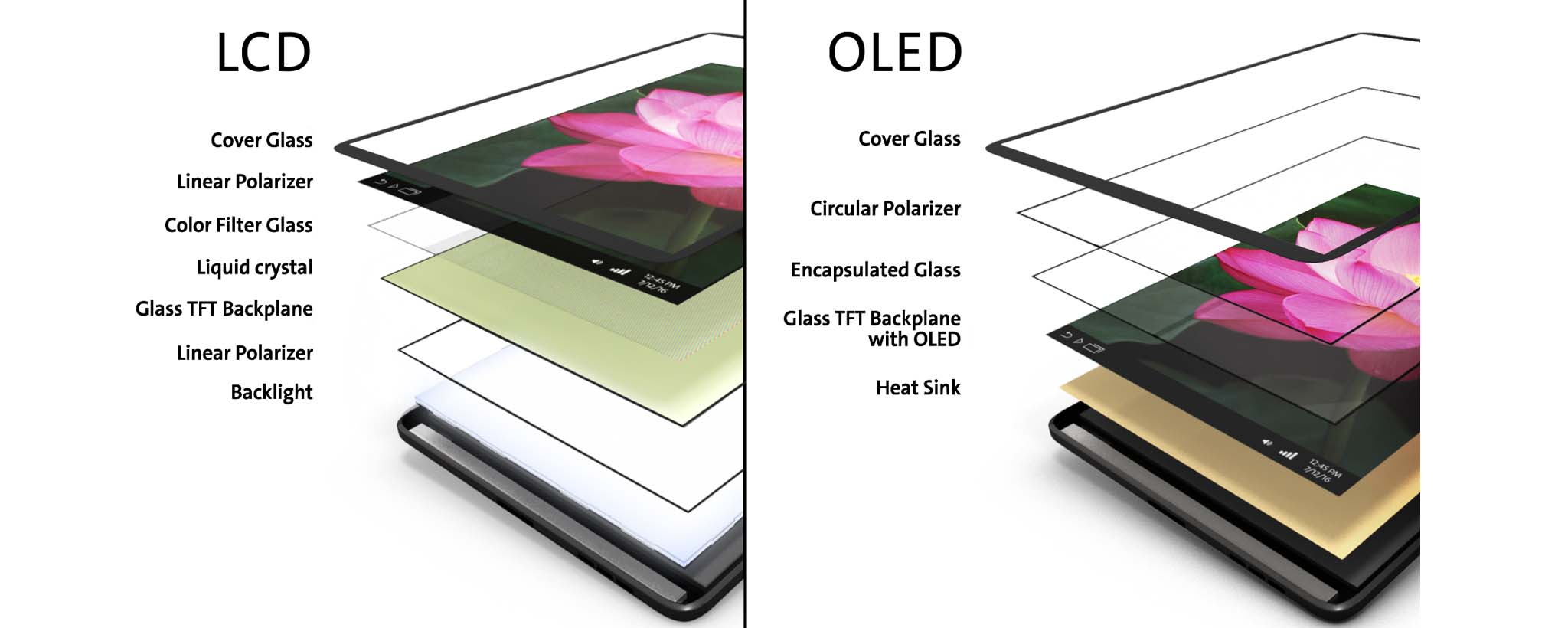

To understand how dramatic an advance OLED is, you first must know that all flat-screen TVs before the OLED required there to be a light source (called a backlight) inside the TV, shining a white light through the LCD (liquid crystal display) panel that most of us just think of as “the screen.” You also have to know that a flat-screen TV’s screen is made up of thousands of tiny points of light, known as pixels (for “picture elements”), each of which is capable of producing almost any color from the white light shining through it by combining red, blue and green sub-pixels in the right proportions.

The difference the OLED introduces is not just a matter of the type of light used, or the color, or where it’s located. The difference is that an OLED TV does not need a light source inside it at all—or rather, the panel is its own light source. Each pixel (meaning each sub-pixel, alone or in combination) emits light when electricity is applied to it.

This is a fundamental change in the way a TV creates an image, and the differences it introduces are dramatic. For instance, before you even turn on the OLED TV, you will notice how thin it is. This is simple geometry: Without the need to include a source of light inside, the chassis can be made much thinner.

Of course, the absence of a backlight not only make the TV thinner, but lighter as well, introducing smaller, minimalist mounting options such as LG’s Picture on Glass design, which virtually eliminates the gap between screen and wall.

When you do turn the unit on, you will immediately notice how deep and dark the black levels are on an OLED. These improved blacks are due to the lack of a backlight. Since each pixel provides its own light, black is produced by simply switching the pixel off. These dramatic “true” blacks have, of course, the added effect of making colors pop, even more than the state-of-the-art image processor inside the TV has them doing. OLEDs also excel at reproducing HDR content, due to the naturally high contrast range introduced by the deep blacks. Viewing angles are also enhanced in an OLED; there is almost no such thing as a bad angle when watching one.

OLEDs have other advantages as well. Gamers will appreciate that OLED technology allows for faster response times, just about eliminating the risk of lag or digital artifacts during fast-moving sequences. In fact, as OLEDs become more advanced, previous limits on response time will be blown out of the water, with refresh rates up to 100,000 times a second now possible. And due to the lack of a backlight, which is an inefficient form of lighting compared to organic luminescence, this superior performance will add less to your monthly electric bill than a traditional LCD panel.

Now, like any new technology, there will be some drawbacks and features that are not fully developed yet. Most of these will be overcome by the continued manufacture of this new type of TV. One such problem is the cost of manufacturing an OLED, compared to an LCD. Five years after the mainstream introduction of OLED TVs, a 55” OLED still costs almost $1,000 more than its LCD equivalent. As more and more OLEDs are produced, and their superior picture becomes more the industry standard, this price discrepancy—the same you see with any new technology—will decrease.

So too will the problem of OLEDs having a shorter lifespan than an equivalent LCD. The natural lifespan of luminescent pixels gives rise to this phenomenon, which is exacerbated by the fact that the sub-pixel degradation over time is not uniform—blue pixels lose their brightness more quickly. This means the OLED will not only lose brightness over time as their LCD counterparts do; the color balance will also be thrown off as the blue sub-pixel dims more quickly than the red and green ones. Currently, an OLED has about half the lifespan of an LCD. This will have to improve if OLEDs are going to take over the mainstream market position now enjoyed by LCD TVs.

One important weakness OLEDs share with LCDs is audio quality. The thinner you make a TV, the flatter you must make the speakers to fit inside the chassis. And as any audio designer will tell you, small speakers cannot reproduce full-frequency sound. The smaller the speaker, the more low-frequency performance will suffer, leaving your sound tinny and lacking in punch. This drawback applies to OLEDs as well. Different manufacturers have tried to remedy this weakness, each in their own way. LG offers a high-end W model, that ships with its own premium soundbar featuring a thin ribbon cable to connect to the TV. Sony offers what is clearly the most innovative workaround with their Acoustic Surface Audio design, which turns the outer surface of the screen—the whole screen—into a vibrating resonant surface delivering full-range stereo sound. But for most OLEDs, the same audio advice applies: If you don’t have a home theater audio system in place, your easiest, least expensive option is a soundbar. (Keep in mind that any brand of soundbar will work with any OLED, and that the companies that make the best speakers are not often the same companies that make the best TVs.)

OLED televisions deliver a markedly superior picture, in a form factor that is thinner, runs cooler, and costs less to operate. Their main drawbacks—lifespan and manufacturing cost—will diminish steadily as market share increases, which is likely, due to the sheer quality of the delivered image. For these reasons, we should all be ready for OLED to become the default consumer choice in TVs, most likely by 2025.